Hard Candy

18APR

Maggie McMuffin examines the online misandry movement in her breakdown of David Slade’s Hard Candy.

Let me talk to you about the word misandry.

The modern misandry movement began on tumblr about, oh, four or five years ago. While it is now being bandied about as fact, as the opposite of feminism, it was actually started by Men’s Rights Activists. They were screaming at politically correct “tumblr social justice warriors” (a phrase now used exclusively to insult people) and calling them misandrists; they hate men, they want them all to die, female superiority reigns supreme!

At first there was pushback. No, that’s not what feminism is. No, that’s not what womanism is either.

And MRAs, they just kept fighting. Saying any request a woman made for safety or any criticism of harassment or rape culture was proof the dawn of man had ended long ago.

The response was to go “Actually yeah, fine,” and to fucking brand that shit. Misandrist art, bright and sparkling. “Fashionable misandry” became a popular tag, consisting largely of mermaids and hot pink self-defense items. We took those accusations and parodied them, creating male tears coffee mugs and “Fuck you, pay me” cross-stitches.

Which of course led the MRAs to point more fingers and yell that this was proof of them being correct!

So we pushed harder. “Dead Men Can’t Cat Call.” “Kill All Rapists.” “Valar Morghulis: Yes ALL Men.”

Fine, we said. You want to say we call death to all men. We’ll say that now. We’ll be the biggest worst thing ever and we’ll do it in six-inch heels!

But of course that just made the MRAs more convinced of our blood lust.

And we gave up, tired of the joke, and said “Actually…we do sort of hate men.”

Not All Men.

We never said that.

(There’s actually an interesting time in the misandry movement where intersectionality was called in and white women were told by POC not to say kill all men because white women still have the ability to enact violence on black men and also where do trans men fit into misandry and what about non-binary people who present as masculine and could butch women be misandrists too because is this about men or about masculinity and it’s actually a very fascinating online movement I hope gets studied one day.)

Anyway.

By being strawmanned, many of us were pushed to the point where we did just openly admit that, yes, we hate men as a concept. Not every man. Not each individual. But in terms of the patriarchy? In terms of gripping keys because a man is following you at night? In terms of not knowing if some guy will roofie you? In terms of “Oh, he’s just picking on you because he likes you”? In terms of having multiple stories of relatives, teachers, strangers, boyfriends, friends, classmates, bus drivers, cops, whatever doing anything from whistling at to raping us and being told that was our fault because of whatever arbitrary rule we managed to break that day?

Well, yeah. We kind of hate men.

But what that meant was we just don’t trust you. Trusting men can’t be the default because men have victimized so many of us and gotten away with it. We are told to fight one another, that girls can’t get along, that Mean Girls is so true to life, but most of us have never been systematically attacked by women the way we have been by men. Sure. Women can assist in that. Women can bully. Women can physically and sexually assault. Again, we never said that wasn’t true.

All we said was that we reached a point where we’ve got to parody the idea of hating men or we’re never going to make it in this world. We need to laugh so we don’t cry. We need to actually empower ourselves to call shit out even though it’ll get us called a bitch.

And unfortunately, that’s lost. Misandry is held up as being a real thing on par with misogyny and it just isn’t. Not in a world where a man’s worst fear is that women will laugh at them and a woman’s worst fear is that a man will kill her.

As the old (I mean four years is old in internet time) adage goes, “Misandry irritates; misogyny kills.”

And that’s where I’m coming from in thinking about Hard Candy.

Because I remember being 15 and watching that with my dad (who is legitimately “kill more rapists” than I am, or at least more “kill my rapist” than I am) and us talking about how overblown the film was. Like, we both kind of thought it was cool. A film about a 14-year-old girl who seeks revenge on a child rapist/possible murderer. But, wow, does that film not make it clear she’s a hero. I still run into people who claim that the movie was good and they totally agree with her, “But is she any better for pretending to castrate him and making him kill himself?”

Which echoes what I have been told, if I express fantasies of bad things happening to my abusers. Bad things I would never actually make happen or do myself. That if you fight hate with hate or violence with violence then, obviously, you’re just as bad. If you strike back against someone who struck you first, well, you’re just as evil.

And that’s really not a good mentality when discussing things like pedophilia.

Like, no. There are not two sides to that issue. We have a man raping a child, and we have a child being raped. If you play devil’s advocate to any degree in that, you are a horrible person and I hope your mother shames you in her will.

But that’s the thing! People are totally allowed to play devil’s advocate on topics like this and get upset if people call them out for their hypothetical little argument (seriously, men do this all the time when rape culture comes up on Facebook), but if a member of an oppressed or marginalized group has a revenge fantasy, suddenly they are the person in the wrong and should be ashamed of themselves.

So I am going into this film hoping, really hoping, that it’s a more balanced narrative than I remember. That people were just misreading it. That it will be a great escapist fantasy where Ellen Page is gonna decimate online predators with her freckles and wit.

First off, I want to say that I don’t see how anyone can come out of this movie thinking it’s being presented equally. Because while Hayley’s methods of getting information from Jeff go from harsh to deadly, Jeff’s creep level does the same.

We open with an online chat between thonggrrrl14 and Lensman319. There’s flirtation, sexual innuendo, and then a decision to meet in an hour that’s prompted by thonggrrrl who insists she is NOT a baby because she reads Zadie Smith. But when we fade to a diner, we find someone who is very much a child, chowing down on tiramisu and chocolate that Jeff is more than happy to wipe off of her lips before offering to buy her more.

I mean that. Scene one and dude is offering to buy her candy. Also a T-shirt if she promises to model it for him.

The scene was triggering, if I’m being honest. About a 2 on my scale. Maybe it’s because there were too many similarities between Jeff and my older abusive ex (including a similar online handle, as my ex’s was and is photoj99), or maybe it’s because I came of age during AOL chatroom scares, or maybe it’s because there is no reason a 32-year-old should be meeting a 14-year-old to hang privately, but for whatever reason I went into the rest of the movie with my mind made up about Jeff being a bonafide creep.

He pulls out all the classic lines: He tells Hayley she’s so mature, she acts older than her age, he can’t believe she’s so interested in reading, yadda yadda NOPE. And the thing is, while Ellen Page was 19 during filming and while I know my father and I agreed ten years ago that this character didn’t read as a real 14-year-old, she totally reads as one in this scene. Ellen Page has super-cropped hair. Not an attractive pixie cut, but a really boyish chop that highlights her freckles and her nervous laughter. While we later learn Hayley is duping Jeff so she can seek some vigilante justice for a missing girl named Donna Mauer (whose poster hangs over Jeff and Hayley’s first meeting) you would never know it here. Hayley may read, she may like Goldfrapp, she may have a big vocabulary, but she’s not confident. She’s unsure, timid, not smooth at flirting, and Jeff is just eating it up and being charming as hell without crossing any huge lines. Patrick Wilson plays Jeff as someone so assured of their own goodness that clearly there is nothing wrong with him taking Hayley home and offering her a screwdriver.

After a tour and Hayley saying she won’t accept a drink not mixed herself, the film shifts to the revenge fantasy we’ve been warned about. Over the course of the next hour, Hayley trusses Jeff up, reveals she’s basically stalked him, and tortures him for info about his pedophilia.

Jeff maintains he can’t be a pedophile or someone who hurts children, because he’s never slept with them. But as a photographer, he is able to photograph half-naked minors and then hang those blown up pictures in his house “as part of my portfolio.” Never the “poignant” and “important” nature shots for conservation agencies, just the “half-naked nymphs,” as Hayley puts it.

In fact, Hayley picks through all of Jeff’s arguments that he’s not a monster until eventually he is left with the one argument that still somehow serves as a legitimate argument in courtrooms:

“Come on. You were coming onto me.”

And while we have half a movie to go, Hayley launches into a monologue that hits home why that’s not an excuse.

“That’s what they always say, Jeff. Who? The pedophiles. ‘She was so sexy,’ ‘She was asking for it,’ or ‘She was only technically a girl; she acted like a woman.’ It’s just so easy to blame a kid isn’t it? Just because a girl knows how to imitate a woman does not mean she is ready to do what a woman does. I mean, you’re the grown up here. If a kid is experimenting and says something flirtatious, you ignore it. You don’t encourage it. If a kid says ‘Hey, let’s make screwdrivers,’ you take the alcohol away and you don’t race them to the next drink!”

But here’s the thing. Rape culture extends to children. A girl going through puberty early and growing breasts makes it easier to say her clothing is provocative even though it’s the only clothing being sold in her size. Children pole dance in beauty contests and people talk about how sad they are before they think to blame the parents who selected and choreographed those routines. A story comes out about David Bowie (and so many other rock stars) sleeping with 14-year-old groupies, and anyone who calls that statutory rape is branded as someone forcibly removing the agency of those girls. Lolita is sold with a pull quote on the cover proclaiming it “The only convincing love story of our time.”

It is easy to blame a child.

And here’s the thing: HAYLEY ISN’T WRONG ABOUT JEFF.

Because here the movie gets more personal, where Hayley begins to ask about the missing Donna. Even through a highly believable but ultimately fabricated castration, Jeff insists he knows nothing about Donna’s disappearance. He just…has a photo of her. And has met her. Because Jeff has a history of going online and specifically meeting 14-year-old girls and impressing them with wit and also lies. No, seriously. Hayley calls him on Googling every band she mentions and pulling quotes from Amazon reviews. He has a system.

Hayley taunts him and mocks him, calling him lonely, threatening harm but never murder. Mostly, she focuses on a woman named Janelle who Jeff used to have a thing with and is still in love with. Like, he saved all her letters. The date of their “first time” (whether a photography shoot or having sex) is the code to Jeff’s child porn safe.

None of Hayley’s threats work. Not ruining his life, his career (which Hayley argues is a false argument anyway because Polanski), calling the cops, throwing him in prison. Through all of that, Jeff might cry and beg, but mostly he shouts he’s innocent or calmly offers Hayley help. That he’ll hold her, that her parents must not care about her but he sure does and understand everything…

All of that crumbles when Hayley threatens to tell Janelle and ruin any chance Jeff ever has of getting her back.

So he admits to Hayley that he didn’t kill Donna.

But he watched.

That doesn’t make him so bad does it? It’s not like he killed her or raped her.

“I just wanted to take pictures.”

But after this, Jeff is ready to go. He manages to get free, but with Janelle on the way and Hayley packing proof, he’s ready to just kill her. Instead, she convinces him to hang himself after he gives up the name of Donna’s murderer, thinking that by siding with Hayley’s vigilantism he’ll be safe.

“I know who he is. It’s funny. Aaron said you were the one who did it right before he killed himself.”

Here’s what this movie is. While, yes, Hayley is extreme, she’s constantly making good points. Jeff’s only argument is that he never actually raped anyone. He’s just been highly inappropriate and used his career to take photos of naked kids. He was even abused as a child because his aunt thought he molested her daughter! But he didn’t! He just did nothing to stop his much younger cousin from jumping naked all over him!

And people like him exist.

Hayley is a strawman in deeds, not words, but Jeff isn’t. Jeff is real. Guys like Jeff, who skirt the line and trade on charm and handsomeness to not be questioned, totally exist in our world.

And one of the best things about Jeff’s character is that he knows this. “I’m a decent guy,” he constantly says. He’s very careful to never hit on the models he shoots, going online for that. He’s well-liked by his neighbors and does work that’s very admirable.

Throughout the entire movie, he thinks he can have power over Hayley. Even at the end when he turns to force, he thinks he can take her down because he’s a larger man. But Hayley is always ahead of him. During their final confrontation on the roof, he says he’ll get out and find her, her dad is a professor at a famous school, and she’s from a smaller suburb. She throws out that none of that is true. Her name isn’t even Hayley.

And it’s clear that up until this point it had never dawned on him. Jeff legitimately had no idea that a 14-year-old on the internet was just as capable of lying to him.

In the end, even we never learn anything about Hayley beyond she’s got a therapist and also a friend she’s seeing after this. Because teenage girls are screens to be projected on. Society feeds them images of what they should be, things they should do. Jeff and other predators mentally dress them up into the people they need to feel good. Hayley played on this and it was probably the easiest part of her plan.

And THAT is when he gives up and kills himself.

As long as Jeff has his male power to rest on, he thinks he’s good. He thinks he can get out. The only other time he comes close to bending is when he thinks he’s being castrated. And once he learns that didn’t happen, he gets a second wind and is ready to kill, not caring about the consequences. Because he can just say that “she was all over me” when the cops show up.

This is a film about a 14-year-old taking power from a man. This is not a film about a bloody rampage; it is a film about a young woman methodically taking apart a man’s power and ability to defend his bullshit. About her destroying not just his will to live but also his entire concept of how safe he is.

Is it overdramatized? Yes. But no more than a Tarantino film. Is it problematic that Hayley repeatedly mentions she’s crazy, especially since it’s framed as possibly being her one honest moment? Yeah. It’s also just a weird choice. Are the lighting shifts really heavy-handed? YES.

But the film is good and it makes its arguments. And because if people can watch this and still think Hayley was as much a villain as Jeff, then maybe we need extreme films. Maybe we, as an audience, need to be beaten and electrocuted before we can admit that being inappropriate with children is usually far more subversive than violent rape.

Because all of Hayley’s methods only led to Jeff saying she was right while he stabs out the crotch of one of his portfolio portraits. Because even before Hayley made the switch, Jeff was still trolling the internet looking for teenagers to hit on. There is no good and bad spectrum for pedophilia. There is only a spectrum of “pedophile” and “actually raped and killed a child.” There are not two equal sides to child rape and abuse.

So just remember that even if a guy is as charming as Patrick Wilson was beforeWatchmen nearly killed his career, he’s still capable of shitty behavior even if he’s not capable of the absolute shittiest behavior.

Random Thoughts

– This movie was the first time I had ever heard of Goldfrapp and to this day I can’t listen to them or hear about them without associating them with online predators.

– Goddamn I love Patrick Wilson and want to live in the timeline where he hit it big and got to be in a truly interesting adaptation of The Phantom of the Opera.

– Speaking of which, did you know Emmy Rossum was 16 during filming of that and Patrick Wilson was 32? It’s like this film sort of called that out along with all the other shout-outs to Hollywood kind of supporting this sort of thing.

– Ellen Page is RIPPED in this movie. I swear, she’s all muscle in this and they have her running around in a tank top for most of the film.

– An unintentionally humorous thing: During the “That’s what pedophiles say” speech, Hayley puts on Jeff’s glasses and a few lines later she tears them off dramatically while making a point about him.

– This film had a “production dog” and I don’t know why. I figure it probably did about as much work as Sandra Oh and the other two cast members did (about four minutes of collective screen time).

– If you think this sounds like a weird companion piece to Juno, you would be correct! In the ten years since this came out I still have not seen much a difference between Jeff in this and Mark in that. One is just wrapped up in comedy and Sonic Youth instead of drama and Goldfrapp.

- COMMENTSLeave a Comment

- CATEGORIESCrime, Drama, Independent, Thriller

Ten Years Ago: Kinky Boots

15APR

Performer/choreographer/filmmaker Maxie Milieu still believes the sex is in the heel, and reminisces on how queer culture (and transgender politics) have evolved in the 10 years since Kinky Boots first hit theatres.

“Ladies, Gentlemen, and those who have yet to make up their minds.”

There are few things I love in life more than a good pair of shoes. Put on the proper pair and the entire person can transform. Or, as the 2005 film Kinky Boots posits, the kind of shoes a person is wearing can tell you everything about them. 10 years ago I was an isolated teenager ravenously devouring movies at 2 a.m. on our limited BBC subscription that came with our new On Demand trial. For me, Absolutely Fabulous, Coupling, The Full Monty, Billy Elliot, and Kinky Boots all arrived in my life at the same time. For a child raised on pop culture who could communicate almost exclusively in Birdcage and Moonstruck quotes, these films spoke my language. In much the same way as Strictly Ballroom, Romeo and Juliet, and Moulin Rouge comprise Baz Luhrmann’s Red Curtain Trilogy, The Full Monty, Billy Elliot, and Kinky Boots seem to me a complete set of quirky British underdog films. They also would eventually all go on to become Broadway musicals. 10 years ago I didn’t identify as queer, I wasn’t in a relationship with a trans person, I’d yet to do any leather manufacturing, or work as a club dancer or a burlesque performer. 10 years ago I may have just purchased my first pair of heels: teal t-strap peep toes that were glowing brightly at the display in Nordstrom. But here we are, 10 years later. Much like our film’s protagonist, Lola, who retraces her steps skipping across the uneven planks of a pier years after we see her do so in the opening sequence, let’s re-dance our steps. All I hope is that I don’t inspire something burgundy.

When we see Lola (Chiwetel Ejiofor!) on the pier for the opening sequence, we are introduced to our film’s central tenants and trials. As Lola covertly slips on some fantastic red stilettos, glancing back apprehensively to make sure her father doesn’t see, she becomes herself. Embodied in one pair of red heels is the promise of the film: the limitless possibility of becoming yourself. When Lola’s father raps on the window snapping us out of this freeing introduction, dismissing Lola as a “stupid boy,” we are reminded that becoming yourself is fucking work.

We are introduced to our other protagonist, Charlie (Joel Edgerton), via the family business of shoes. We get the clear sense that Charlie, in his shitty trainers, is not invested in this business. When his father dies, he takes over the business realizing it is in severe financial trouble. After making over a dozen employees redundant, he is challenged to find a solution by one of the women he laid off. A chance encounter with Lola in London, where in defending herself Lola accidentally knocks Charlie out, leads to the spark of an idea to make shoes for the niche market of Drag Queens.

After an initial prototype failure, in which Charlie makes the least alluring pair of boots in all the land, Lola gives us my favorite monologue in the film. Disgusted at the burgundy color of the boots and appalled by the utilitarian heel. Lola break it down for us: The shoe is about sex, and the sex is in the heel. YES LOLA! “REEEEEDDDD” she purrs, the boots need to be red. The concept of the steel shank is born and we are off to montage land as provincial Northhamptoners, a shoe factory owner, and a Drag Queen work together to create two feet of irresistible cylindrical sex for the Milan Fashion Show. We overcome stereotypes and prejudices, fight the onslaught of progress (Charlie’s fiancée wants to turn the factory in to condos), and make a damn fine pair of boots.

Scattered throughout the film are Lola’s Drag performances. They act complementarily with the montages of boot-making, knotting together this process of manufacturing with the manufacturing of dreams. It’s a thoroughly enjoyable juxtaposition. Though I wish that Lola was not our sole speaking representative of the Drag and Trans world, as well as the only POC actor in the film, the performances give the film the tone of a spectacular in the way a pure narrative couldn’t do. Lola enlivens the possibilities of the boot-making endeavor and makes it something much bigger than just selling a product to a niche market. The boots are hopes, and dreams, and freedom, and truth, and sex, and desire, and power. When the first pair of completed boots rolls down the conveyer belt and we watch Lola gleefully pluck them up and slide that long zipper up her thigh, it is just pure magic. When she flicks the whip THAT HAS ITS OWN BOOT POCKET up the length of the boot, tucking it snugly in to place, the feeling of satisfaction and excitement is phenomenal. I think if I had a pair of those thigh-high, whip-concealing, RED boots, I could do anything.

Things seems well on their way until Charlie begins to lose his chill. Pushing the craftsmen too hard in his drive for perfection they walk out, leaving the order unfinished. However, the people of the factory come together again to finish the order after they are rallied by our everyman “Don,” who was initially hateful toward Lola but grew as a human being and overcame all his lifelong prejudices in the course of 40 minutes. The order completed, all seems to be going well until Lola invites Charlie to a celebratory dinner and, while she has been “dressing down” in the factory, comes fully glammed out. Charlie hits his own prejudices dead on (gotta watch out for that pesky white male cis privilege always waiting to rear its ugly head) and insults and berates Lola in a way that, 10 years later, I find unforgivable. Charlie and a select few factory people head to Milan, sans Lola. When Charlie’s confesses to his new love interest that he was a douchecanoe to Lola and now they have no models, she challenges him, yet again, to figure something out. Charlie decides to walk the runway alone. In a scene that I’m sure inspired every “Let’s make the models wear dangerously high heels so they fall for entertainment” challenge on America’s Next Top Model, Charlie, quite literally, falls all over himself on the runway. He lies in a crumpled, disgraced, defeated pile, wearing a suit top, underwear and the aforementioned fantastic boots. Mirroring his vision early in the film, while facedown on the catwalk, he sees a pair of shiny red heels glimmering like a vision. It’s Lola! Come to save the day with her choreographed Drag runway extravaganza to “These Boots Are Made for Walking.” Fuck yes, this is what I’m here for. The number is a smash, the factory is saved, and Lola closes us out with one more number (after resolving the tension between her and Charlie).

Thoughts on the terminology used in the film. Kinky Boots uses the word Transvestite or Drag Queen to describe Lola. For where I stand in Seattle, WA in the U.S., 10 years later, conflating Drag performance with Trans identity is a no. While trans performers can and do perform drag, the identities are not one in the same. Transgender would also likely be the appropriate terminology for Lola in 2016. Overall in the film, Lola is described by her chosen pronouns of “she” and “her” except by “Don,” our stand-in for all bigotry and hatred. It gets a little muddy toward the end when our white cis dude (Charlie), after berating Lola as someone who is just a man in a dress and calling her Simon and asking her to show up looking like her passport, leaves a moving message to Lola explaining that he doesn’t know what a man is and complimenting that “she is more of a man than [he] could ever be.” It’s almost as if the film is striving to use “man” as a metaphor. Successful? Perhaps partially. Shoes make the man, man makes the shoes, shoes for a woman who is a man. There’s a great deal going on here. 10 years ago when I watched the film, none of these politics were on my mind. Watching 10 years later, my overall thought is that the film is perhaps even more relevant today as marginalized communities continue to strive for more visibility and equal rights. As technogiants take over our cities and begin to make us artists and individuals redundant. Kinky Boots is a true modern Cinderella story. It confronts the discomfort of our cis characters in a way that makes them reevaluate their suppositions. It does not always do this without sparing Lola discomfort, but it demands that we get to Lola’s level.

Kinky Boots is a well-acted, thoroughly enjoyable underdog film. It hit me more deeply 10 years later as my age and life experience made the trials of the film far more applicable to my life. Progress is churning ahead even more rapidly than 10 years ago. The fantastic elements of the drag performances seem banal and everyday to me in my current burlesque world. The truly uplifting moments come in the character interactions and the truth of the simple and everyday strife of attempting to be true to yourself.

Also, it has enough shots of feet to make my former ballerina heart happy.

Additional Thoughts:

– 10 years later, we are still very fixated on bathroom issues. The landlady that Lola is staying with asks “Can I just ask, are you a man?” When Lola responds in the affirmative the landlady responds, “Ah that’s fine, just sos I know how to leave the toilet seat. I’ll get some biscuits.” Clearly a moment of levity, meant to show Lola acceptance from an unlikely place, highlights the fixation on gender and bathroom. In fact, one of the major emotional scenes of the film takes place in a bathroom. After showing up dressed down to the factory, Lola hides in the men’s bathroom where she identifies herself as Simon to Charlie and recounts her childhood struggles with her father. Clearly gender identity and bathroom use are just as entrenched today as they were 10 years ago.

– One of the most compassionate moments in the film is when Lola and Don are having an arm wrestling competition. Lola is about to best Don when she looks in to his eyes and realizes that this is all he has in life. That his identity is fundamentally tied to this show of masculinity. She lets him win. #masculinitysofragile

– I am not in to 2005 shoe fashions. All strappy, and kind of low heels. No, just not my style. As someone who has a pair of Jimmy Choos, I hate the ones that the lesbian ghost from Hex fanned over.

– The older man, George, who suggests the steel shank, is my favorite side character in this film. He is just so loving to those boots.

– I love that the drag show runway spectacular just leaves Charlie flat on the catwalk while they stomp it out over him.

– Lola, don’t give up your show to work in the shoe factory! Look at that stage! Those lights! The costumes!

– I wish Lola had a love interest.

– I am very sad that the original factory that made “kinky boots” no longer does so.

- COMMENTSLeave a Comment

- CATEGORIESComedy, Drama

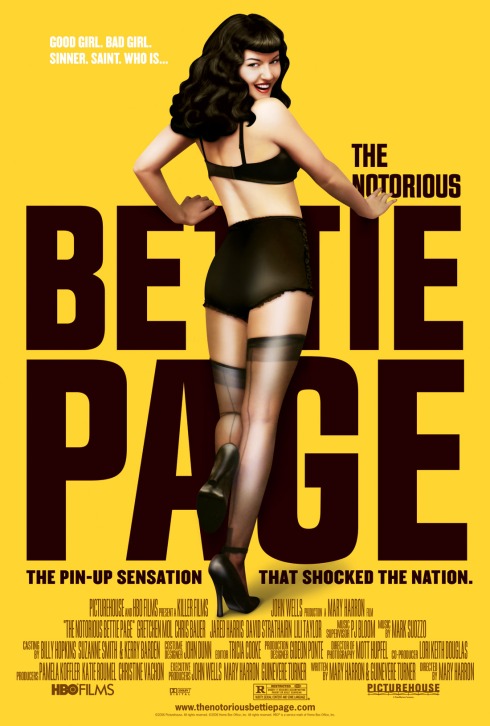

Ten Years Ago: The Notorious Bettie Page

14APR

Sailor St. Claire wonders why, even after twice watching the biopic The Notorious Bettie Page, she feels just as detached from Bettie Page as ever.

The Notorious Bettie Page isn’t exactly a bad movie, but it isn’t exactly a good movie, either. In this way, it’s a very fitting dedication to its subject. Bettie herself may have made a living as a “bad girl” on film, but wasn’t exactly a bad girl at all. Mary Harron and Gwen Turner’s biopic on the raven-haired pin-up queen focuses on Bettie Page as a blank canvas for the projection of other people’s fantasy. Even though a biopic is supposed to tell us something about the subject, Harron and Turner’s film leaves Bettie as an enigma. A religious girl from Tennessee who never wanted to be a teacher, with a natural talent for posing in front of cameras, and no shame about the body she was born into—these are the only three things we learn about Bettie as a person by the end of the film.

I know a lot of people, both in the pin-up/rockabilly/burlesque communities and around the world, wonder why Bettie Page would give up being Bettie Page, and the film does seem to pose an answer to this question. Bettie’s story is framed with the raids on Irving Klaw’s photography studio, and the 1955 hearings which accused Klaw and his wife of distributing pornographic material, especially through the mail in violation of the Comstock Law. Bettie herself waits outside the courthouse, waiting to be called to give testimony, for 12 whole hours, before the court determines she is unnecessary to the process. The film posits that there’s something about her role as a model here—the idea that her voice, her thoughts about any of the things she did on film for the Klaws or other photographers is “unnecessary”—that seems to shift Bettie’s thinking about her work. After the trial in which she is denied participation, she moves to Florida, reunites with Jesus, and becomes a preacher. The final scene shows Bettie telling a stranger that she wasn’t at all ashamed of her allegedly pornographic modeling, but that her God didn’t want her to model anymore, and so she didn’t.

Biopics have a tendency to lionize their subjects rather than critiquing them, and so the detachment with which the filmmakers treat the “notorious” Bettie Page is in some ways very refreshing. The choice to replicate the cinematic techniques of a period melodrama both aids in creating this sense of detachment, I think, as well as actually detaching the audience. Much like the racy photo essays that made Bettie famous, the filmmakers treat her story as a series of images rather than a narrative. As such, we as viewers don’t get much to cling to, which is why even after viewing this film, I still feel detached from Bettie. She maintains her mystery and allure, even though we do become privy to facts about her life: that she was kidnapped and raped in her early days as a model, that a black man was responsible for starting her career (and that she didn’t see a problem with a black man taking photos of a white woman in the 1940s), and that taking kinky photographs for men’s enjoyment was nothing but harmless dress-up fun to Bettie. These vignettes of her early life are presented to viewers via the camera zooming in on a letter to a friend back home, which Bettie grasps in her gloved hands while she waits outside the courthouse at the Klaw’s trial. I thought this was a nice nod to period cinema, and I liked how camera moves like that were paired with a generous use of B-roll shots of the American countryside as Bettie traveled on busses from Tennessee to New York.

The majority of the film is in glorious black and white, save for a few scenes in color—most of which take place in Florida around everyone’s favorite dream femme Sarah Paulson as Bunny Yeager. I watched this film with my friend Maggie McMuffin, and we both had a difficult time tracking what the shift to color was meant to represent. Had all of the scenes in shitty old-timey color been in Florida with Bunny, we would have been content reading them as scenes in which Bettie was being seen as a person (i.e. by a woman) than in the black and white way men saw her. But there’s also a scene in color where Bettie, the Klaws, other models, and some of their preferred clients are all playing croquet somewhere in upstate New York (and then taking “edgy” bondage-in-the-woods shots after the game), and, of course, the final scenes illustrating Bettie’s “conversion” back to her Christian life and new career as a preacher are also in color. So I’m not sure how to read the presence of color. Perhaps they’re meant to illustrate scenes in which Bettie’s making choices for herself, but if that’s true, it invalidates not only how she understands her career as a model, but her actual choice in becoming a fetish model (which as a pretty white woman, she had a lot of choice in).

One thing I think the film makes clear is that the women who worked for the Klaws were not exploited, or asked to perform any tasks that they wouldn’t be fairly compensated for—or for clients not approved by the Klaws themselves. But at the same time, there are many scenes elsewhere that illustrate that amateur modeling is no different now than it was in the 1950s—from the proliferation of edgy bondage photos in the woods, to photographers asking models to do more than they agreed to pay for, it’s as if Bettie Page was on Model Mayhem before Model Mayhem even existed.

The Notorious Bettie Page is a strange pastiche of images from the life of a woman who is better known in pictures than in words, and so perhaps its best to leave her that way, innocent and naughty all at once, decorating Christmas trees in the nude in Playboy.

Free-Floating Thoughts

– Gretchen Moll sure is good at being a bad actress.

– Maggie: “That guy looks like a knock-off Norman Reedus.” Me: “That is Norman Reedus.”

– Jared Harris, better known as Lane Pryce on Mad Men, plays a total scuzzball in this. He looks like Remus Lupin on a bender.

– Jefferson Mays looks terrifying in this film.

– The minute Bettie’s actor boyfriend tells her he thinks her fetish photos are disgusting, Maggie and I both yelled, “Bye, Felipe!” at the screen.

– Not enough Sarah Paulson as Bunny Yeager. I’d have loved to see a more feminist take on Bettie Page that focused on how she and Bunny Yeager collaborated and mutually built one another’s careers.

– Sheriff Andy Bellfleur is Irving Klaw. That one took us a while to recognize.

– I want to live in Bunny Yeager’s house.

– The costume designer for this film did an awesome job. We loved all the 1950s swimsuits and underwear. We loved Bunny Yeager’s sundresses and sensible sandals.

– That holiday pinup from Playboy, where Bettie is decorating her tree while wearing nothing but a Santa hat, is basically the gold standard for Christmas pinups. It is a remarkable photo, and Yeager really does capture something special about Bettie in that shot. I can’t explain why it works so well; it just does.

– Paula Klaw is a hero for not burning all of the images she and Irving shot. Thank you, Paula, for saving the smut you worked so hard to make.

Tags: 10YA, 2006, 2016, American Horror Story, American Psycho, Bettie Page,Boardwalk Empire, Bunny Yeager, Cara Seymour, Chris Bauer, David Strathairn,Gretchen Mol, Guinevere Turner, I Shot Andy Warhol, Jared Harris, Jefferson Mays, Lili Taylor, Mad Men, Mary Harron, Norman Reedus, Notorious Bettie Page, Sarah Paulson, Ten Years Ago, True Blood

- COMMENTSLeave a Comment

- CATEGORIESDrama

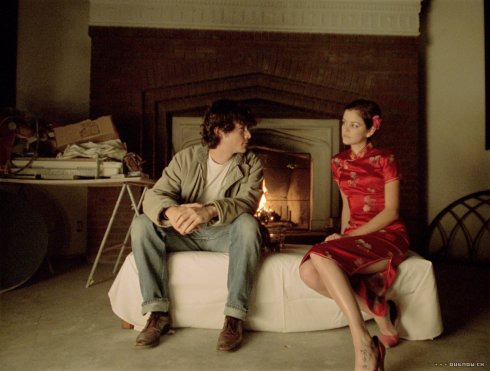

Ten Years Ago: Brick

4APR

Erik Jaccard explores the generic synthesis of film noir and high school dramas in Rian Johnson’s Brick…and makes your editors really want to watchVeronica Mars.

BrickWritten and directed by Rian Johnson

BrickWritten and directed by Rian Johnson

In starting, I would suggest that it is a remarkable achievement for a film to help us see a genre with fresh eyes. Because this doesn’t occur very frequently, it’s all the more surprising when we run face-first into something that seems refreshingly new. We emerge from a cinematic experience energized and enthusiastic, but not even totally conscious of what we’ve just experienced. All we know is that it was some new thing, or some old thing we’d seen a million times, but this time done differently. Unsure of the what or the why, or of how to think of this new thing properly, we can only stop and feel. ‘YES. That. More of that please.’

This is overly dramatic, but it’s also a fair approximation of how I felt after seeing Rian Johnson’s neo-noir high school drama Brick for the first time. It was June and I was living in Edinburgh, Scotland. I’d finished the coursework for my master’s degree, was living on borrowed money, and had nothing to do but spend the following four months writing my thesis. Quite naturally, I was doing everything but that. Instead, I was hanging out with friends, drinking in the sun, running and reading a lot. I was working a little, sure, but mostly I was enjoying the long Scottish summer days and reveling in notion that I didn’t have much to do except eventually try to say smart things about some books. So, with all of this time on my hands, I started not only going to movies on my own, but taking chances on the smaller, independent films I’d be less likely to convince my friends were worth seeing. And so, on a fine early summer evening I trotted down to one of Edinburgh’s most charming arthouse cinemas—The Cameo—and watchedBrick. Later, I emerged into the listless purple dusk outside and stood there, feeling my freedom and smiling ear to ear at the cool new thing I’d just witnessed.

As any who have seen the film know, the central conceit behind Brick is the transposition of the hard-boiled detective story—think Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon—into the context of a high school drama. On first viewing I found this idea to be very, very clever. In much the same way that I was bowled over byEternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind’s novel fusion of science fiction and romantic comedy, Brick’s blurring of generic boundaries helped me see each component differently. On the one hand, by setting a noir storyline in a high school, Johnson’s film brings much-needed levity to a hard-boiled genre that too often retreats into superficial shadows and straight-faced genre clichés. At the time I’d forgotten just how funny hard-boiled detectives can be, and Brick, as I explain in more detail below, is actually a really funny film in a lot of ways. On the other hand, the ominous tone and subjective uncertainty of the noir thriller ironically illuminates some of the deeper recesses of the high-school flick’s often frivolous or basely comical rendering of teenage life. The best examples from the hard-boiled film noir canon crackle with visual and verbal ingenuity, and Brick, because it stays so true to the ethos of those earlier films, lends the tired high school drama both a new gravitas and also an electric, memorable verve.

Johnson notes in interviews that he’d been working on the idea for Brick since the late 1990s, but that he’d had trouble gaining traction with reticent studios understandably wary of taking on such a unique project from an unproven director. This probably makes sense, but then again, so does Johnson’s idea. For one, there’s a lot of exploitable overlap between character archetypes in the two genres: the wise-cracking, resolutely determined detective isn’t that far from the sarcastic social misfit giving the popular kids the fish-eye from across the cafeteria; the hard-working PI sidekick easily transitions into the diffident but resourceful nerd; the femme fatale is a differently drawn, and more mysterious version of the teenage drama queen, and so on. Second, the heavily stylized underworld argot of the detective narrative doesn’t seem that unnatural coming from the mouths of teenagers, who already speak in their own blurry and sometimes incomprehensible subcultural patois. Third, and this is a point I touched on long ago in my June 2011 re-view of The Fast and the Furious, both genres are inherently concerned with social dynamics, and particularly with codes of inclusion and exclusion. Just as detectives must operate in the seams between various social strata in order to determine the truth of their case, so, too, must the high school hero learn to navigate the various cliques and clubs—and the power dynamics which separate them—to determine the best route to achieving his or her goal. In doing so he or she often lays bare the unwritten rules and privileges by which some are elevated and others banished. Finally, and this might be the most obvious point, teenage life is full of both real and perceived drama, bickering, back-biting, deception, and betrayal—not unlike the detective story. Adult life contains its share of these things, too, but for teenagers it often seems like a much bigger deal, partly because the average teenager’s world is so small and partly because teens lack the maturity and perspective necessary to see their drama in context. As a result, the teenage years can often seem dark, frightening, and momentous, full of hidden motivations and secret dealings, insecurity and doubt, fragile alliances and naked power plays. (This is also, I believe, why the high school setting works so well a locus for Shakespearean tragedy.)

This is a long way of saying that in 2006 I found Brick to be a thoughtfully conceived, intelligent, and entertaining new take on established forms and that I enjoyed it all the more because it gave me the feels in all the ways I discuss above. While I’m not quite as invigorated ten years later—novelty does wear off, after all, to be replaced by newer novelties—I’m every bit as inclined to rank Brickamong the better and more adventurous independent film projects of the 2000s. Watching it this time around I again appreciated its ambition, eagerness, and commitment, even when these qualities sometimes muddle the successful execution of the film’s larger premise. All in all, Brick stands the test of time, and for the next few pages I’ll attempt to explain why.

For those who haven’t seen the film, or haven’t seen it for ten years, here’s a brief precis of the plot. Brendan (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is a social misfit at his Southern California high school. He eats lunch every day by himself behind the school, weary of the world but unable to disengage from it completely. On day, his ex-girlfriend, Emily (Emilie de Ravin) calls him mysteriously and tells him she’s in big trouble and needs his help. Before she can explain fully, she’s cut off, leaving Brendan with only a handful of vague clues. A few days later Brendan finds Emily dead in a stone culvert which also doubles as a clandestine meeting spot for the area’s affluent, popular crowd. Determined to get to the bottom of what happened, Brendan starts tracking down her known acquaintances. He eventually ends up knee-deep in the school’s cultural underworld and must deal with a shady cast of characters of whom few, if any, can be trusted. There is the devious upper-crust femme fatale, Laura (Nora Zehetner), who at first seems only interested in helping; there is the tweaker burnout, Dode, who Brendan learns had been Emily’s most recent romantic attachment; and there is the vamp-vixen actress character, Kara, whose constant duplicity confounds Brendan’s quest for answers. These high-schoolers lead Brendan to the area’s local drug lord, ‘the Pin’ (Lukas Haas) and his truculent henchman, Tug. Through a fairly tense sequence of proverbial twists and turns, Brendan grows wise to the real culprit behind the murder and, ultimately, to the larger systems of power and perversion underlying Emily’s death.

Now, one of the things I noticed this time around was the way the film’s setting and aesthetic plays against and softens some of the moodier textures of the conventional noir film. One of the disturbing pleasures of the latter is a shadowy grittiness in tone, which in movies like Double Indemnity or Touch of Evil is produced in part by stark contrasts between light and dark, and also by a kind of visual claustrophobia of setting (bequeathed to the genre by German Expressionism). By contrast, Brick is relatively expansive and incandescent. While it certainly references noir’s cloistered aesthetic, it also undercuts it in refreshing ways. For one, Johnson chose to set the film in his hometown of San Clemente, California, a beachside community in southern Orange County. This, combined with the fact that teenagers are afforded very little private space of their own, means that much of the film takes place outside, and is predictably shot at wide angles capable of expressing the long expanses of blue sky, and the rectilinear parking lots, football fields, and well-lit outdoor hallways typical of the SoCal high school flick. Such moments expand the viewer’s perception of the characters because it widens the aperture in which their dramatic potential is understood. Unlike the earlier films, where lighting and setting work metaphorically to express an entropic sense of collapse or psychological pressure, Brick evokes the infinite and open-ended. For every shot of a gloomy lair or darkened culvert, there is a corresponding escape into open space which disrupts stock conventions of noir filmmaking. This makes a lot of sense when you think about it. Teenagers are notoriously moody, if not gloomy, but this gloom is motivated as much by fear and uncertainty about the open-ended future and about understanding who and what one is going to be when they get older. This time around it was clearer to me that Brick’s visual aesthetic carefully recalibrates noir conventions less to emphasize the beastly horror underneath consensus social life—the darkness ‘in here’—and more the terror of the unknown ‘out there.’

I was also struck this time by the film’s humor, which I definitely don’t remember noticing as much the first time. While Brick plays around with some of the hard-boiled tradition’s characteristic dark comedy—Brendan’s lippy office exchange with the Assistant Vice Principal is a great example of this—its comedy derives mostly from the ironic juxtaposition of conventional teen movie settings and scenarios with the deadpan seriousness of its noir plot. Consider: the hard-boiled noir film offers the viewer glimpses of danger and intrigue uncommon to ordinary lives. Indeed, the strangeness of the seedy worlds depicted and the grave nature of its criminal plots are part of the genre’s appeal. At the same time, the conventional teen movie is utterly ordered and ordinary. Even when teen movies depart from the status quo they often do so only to return to it later, perhaps with the balance of power shifted in favor of the protagonist. But inBrick these two registers co-exist and produce this gleeful estrangement of both noir and teen movie tropes that keeps you oscillating between tension and humor.

For example, in order to arrange a meeting with the film’s mysterious drug lord—‘the Pin’—Brendan must fight not a group of adult henchmen, but one of the school’s entitled ‘upper crust’ loudmouths in an afterschool parking lot. There’s the crime narrative element: Said loudmouth is one of the Pin’s primary dealers, so Brendan has to get through him to get to the Pin. But there’s also the teen movie trope: the clearly mismatched fight between scrappy loner and muscular jock, the former forcing social recognition by taking on its officially approved proxy. When the meeting finally happens, Brendan is driven to an ordinary suburban house, where the Pin’s mother (he lives with his parents) frets in the background about what kind of juice to offer the boys, seemingly unaware of the gravity of the conversation about to take place. Later on we see the Pin being driven around in a Chevy Astrovan (presumably also his parents’) with the back fitted as a model of his basement den. And even with daylight glaring through the windows, the Pin keeps his ominous lamp (complete with exotic shade), seemingly for dramatic effect. The scene draws the noir-esque imagery out to such an extent that we can’t help but laugh at it, literally exposed by the light of day as a kind of staged farce. This wouldn’t work if the film didn’t fully commit to both of its component genres, but thankfully it does. The actors play their parts with such deadly seriousness that you often forget that what you’re watching is actually really silly.

My favorite comic moment is the following exchange between Brendan and the Pin on the beach near the Santa Monica Pier. Having exhausted their shop talk, the two sit down, Brendan obediently behind the boss. The Pin speaks first:

“You read Tolkien?”

“What?”

“You know, The Hobbit books?”

“Yeah.”

“His descriptions of stuff are really good. Makes you wanna be there.”

Now, we like to think of our crime-movie villains as having some kind of villainous panache, whether that be intellectual or physical, or even sexual. We’re used to them having something that sets them apart, something to lend legitimacy to their power—even if it’s something horrible, like their willingness to dip victims in corrosive acid. But in this scene everything we know about the Pin’s noir archetype (noirchetype?) is so humanized that it becomes impossible not to see him as an unconfident boy attempting to bully others in his own little corner of the playground. Silhouetted against the setting sun, having a moment on the beach with his new bro, he spouts a line that sounds like the limp crescendo to a really bad paragraph in a freshman English paper. Maybe I laughed because I’m a person who sometimes has to grade bad English papers. However, I also just stopped and thought What? You can’t say that! You’re a mysterious urban myth, a veritable enigma of the streets! In no conceivable universe does a tough as nails noir gangster say “His descriptions and stuff are really good. Makes you wanna be there.” It drains all stylistic menace out of the scene and, for just a moment, you see the humans in front of you as vulnerable, uncertain people rather than narrative archetypes.

There is, then, a lot of poignancy to the film’s humor, too. I couldn’t help but picture the end of Big, when Tom Hanks shrinks backs down to his teenage self and we see a shy boy walking down the street in a man’s suit. For the majority of that film the point is to laugh at the magical premise of a boy being transported into a man’s body and then doing childish things in adult form. We feel for him when he’s afraid, alone in the city, crying for his mother, and we delight in his playfulness and creativity in a world full of practically minded adults. We laugh because he’s so out of place, and because it’s a comedy the film nudges us to take this slapstick contrast as the primary point. Yet, there’s a darker irony here, too, and it’s produced by the nagging feeling that Josh is not, actually, that out of place. In fact, as he moves through the corridors of corporate power in New York we come to learn that he is surrounded by a variety of teenage archetypes living in the guise of adults. There’s the jaded popular girl, tired of all the stuff-shirted boys fluttering their feathers around her; there’s the older protector-figure, acclimated to the unforgiving nature of his world, yet willing to take a chance on the underdog; and there’s the aggressive bully, attempting to gain power and influence over others, no matter the cost. These, too, are kids wearing grown-up clothes, just as real-life gangsters, CEOs, and politicians are versions of other playground archetypes whom we’ve convinced ourselves are somehow different or more important because they’ve achieved adulthood. When a child collects all the blocks in one corner of the room we assume he or she is doing it because they haven’t learned to share; when adults do it, it’s because they’re talented, or strategic, or intelligent. Now, after that lengthy digression, here’s the point. The first time I saw Brick I marveled at the humor in people doing grown up things in kids’ bodies; this time I saw it the other way round, as all the grown-ups in my world continuing to do kid things, but convincing themselves it was something else. It isn’t as much that the Pin is a kid acting like a grown-up, though that is literally true, but rather that all the other big-shots are grown-ups who have convinced others their childish behavior is mature, and thus worthy of respect.

If it seems like I’m using the film to talk indirectly about class, it’s because my next point is about class. Watching Brick for this re-view, I kept seeing class dynamics pop up where I’d previously missed them. After thinking about this for a bit, I decided this was because I’d received the film in terms passed down to me by secondary interpretations of the film noir as a genre. For example, when I watched it the first time I was aware that the genre was more often than not interpreted in the psychoanalytic language of unconscious anxieties and desires, and that it thus foregrounded crises of sexuality and gender, and particularly female representation. To this point both of these hypotheses have generally made sense to me, given the genre’s emphasis on dark spaces, damaged anti-hero men, and the infamous and ubiquitous archetype of the femme fatale. To be sure,Brick features all of these things, and one could not be blamed for interpreting the film in light of these concerns. Yet, this time I kept coming back to class. So I did some light background research and eventually came across Dennis Broe’sFilm Noir, American Workers, and Postwar Hollywood (2009), which provides an alternate reading of the conditions of emergence for the genre. Contra conventional academic readings of noir, Broe situates the genre in the historical context of postwar labor unrest, the politicization of Hollywood, increasing corporatization, and middle-class anxiety. In sum, he argues that the genre, at least for a brief period between 1945-1950, was a vehicle for the expression of leftist political values and oppositional artistic energies. Rather than see the male protagonist of the noir film as expressive of a masculinity in crisis (though it seems to me difficult to abandon this idea completely), he views him in terms of class struggle. I haven’t watched enough classic film noir to either confirm or refute this reading, but its suggestiveness led me back to Brick, a film whose teen movie element more consistently drives the class element to the fore.

We’d probably all agree that the teen movie, whatever its sub-classification, often foregrounds social stratification, and that this representation often stands as a metonym for the society at large. The allure of the popular kid is, much as in real life, often linked directly to an obvious affluence, and it is in contrast to this ‘upper crust’ element that the teen film’s protagonist is called to define him or herself (at least initially). Class anxiety is thus coded into the architecture of the genre and a character’s ability to succeed often depends on his or her awareness of social fault lines. Film noir, if we accept Broe’s claim, most often expresses this tension symbolically. Brick, however, because it so consciously blends its noir element into the teenage landscape, can’t help but illuminate it.

The various social strata of Brick’s high school environment are, just like adult manifestations of social exclusion, defined by different ‘worlds’ (as Emily reminds him, “I’m in a different world now and you can’t keep me out of it”). To cross from one to the other is to violate the informal codes of inclusion and exclusion which regulate boundaries and keep the privileged and the undesirable from mixing. The teen movie most often takes such rules for granted, even if it ultimately works to subvert them in a moralistic inversion of real-world outcomes. Because it is a teen movie, so does Brick, at least superficially. For example, we can glimpse the firm class boundaries in both scenes where Brendan is interrogated by the school’s resident braggart, Brad Bramish, who questions why the former is hanging around spaces where he clearly ‘doesn’t belong’ (i.e. around the rich kids). Because it is a noir film, however, it also forces to the fore a protagonist who exists outside the social spectrum and who, no matter what crime he is tasked with solving, also serves to expose the complex machinations by which social order is reproduced. This is, of course, not what Brendan consciously sets out to do. His main order of business is first to help, and then to avenge Emily, whose fatal mistake is to naively assume social mobility is possible. This hope blinds her to her own instrumentalization at the hands of the wealthy and mysterious Laura and ultimately leads to her death, thus setting Brendan in motion and turning the orderly social universe of the film on its head.

The film’s class awareness is bound up with its cynicism, which is one way in which it really does mimic the emotional morass of the classic film noir. The smartest and most successful characters are those who are aware that they are multi-purpose parts in a larger class system of which most are unaware. While this system cannot be controlled, it can be manipulated for gain. Those who lose in the film are the ones, like Emily, or her tweaker boyfriend, Dode, who hold out hope that a moral resolution is possible, that love or good or justice will prevail. The film’s primary characters (i.e. the ones that don’t die) recognize that this hope is illusory, that they can either reject the system and face lonely exile (like Brendan) or game it at the expense of others. True to noir form, the latter condition is most aptly characterized the film’s two femme fatales, but particularly by Kara, the vamp-chameleon archetype.

I found Kara fascinating this time, because of how clearly the film wants us to see her as perhaps the most socially conscious of all its characters. Never shown outside of a theater setting (and always in various costumes), Kara understands that not only her success, but also her survival, depends on a willingness to play a variety of roles. In traditional reading of film noir Kara would be the protean female whose ability to perform multipole identities exposes the internal schisms at the heart of the male protagonist’s seemingly stable masculine self. Working within this paradigm, Brendan’s ritual disrobing of her near the film’s end would mark the return to normalcy; in stripping her down to her female body, he deprives her of the ability to tell the lie to his own performative masculine identity.

I focused in this scene on the moment when Brendan smashes the mirror over Kara’s head. We hear the glass shatter and then the shot pans up to reveal Kara, in full kabuki makeup, starting grimly upward against the shattered mirror. If we see the mirror as representative of Kara’s power to reflect to the world the identity she wishes it to see, then Brendan’s destruction of it would seem to shatter (sorry, bad pun) and reveal the core identity beneath the surface. Yet, what we see is what is behind most mirrors: nothing. This is where things got a little dark for me, because, as I noted above, while Kara is cynical, she is also intelligent. She has learned how to play a game she’s destined to lose by mimicking the means by which it sustains itself. We’re taught to play roles and we play them. In high school these roles have complex social determinants, but they often revolve, consciously or unconsciously, around class. Kara knows this, which is why she’s not entirely disingenuous when she coyly asks Brendan whether he really wants to know what he thought he wanted to know: There is nothing behind the glass. No redemption is possible for Brendan or Emily, for the Pin or his poor, musclebound hamster henchman, Tug. There will be no redemption for Laura or her victims. The authorities will do their thing and order will be restored superficially, but only at the cost or re-obscuring the more fundamental social issues the teen movie papers over in the name of entertainment. To say any or all of this is not to say that I reject earlier readings of film noir that Brick is doing the genre a disservice by opening it up to an analysis of this kind. In fact, I think this fresh emphasis on class is one of the things that makes the film more interesting than most stock in trade entries into the tradition. Had Johnson not chosen to do something different, we probably would have been left with a very good film working a very familiar premise to moderately successful ends. But it wouldn’t have been nearly as memorable, exciting, or intellectually stimulating.

- COMMENTSLeave a Comment

- CATEGORIESComedy, Crime, Drama

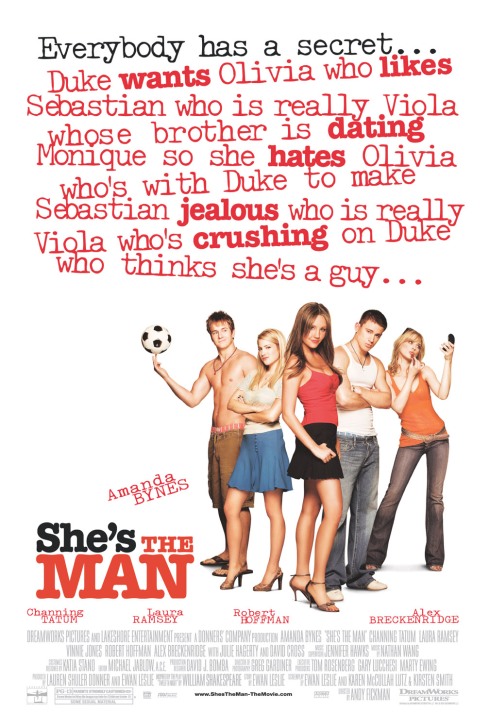

Ten Years Ago: She’s the Man

18MAR

Kiki Penoyer helps Amanda Bynes go undercover to dismantle the patriarchy from within with She’s the Man.

One of these people ends up on Mad Men.

Ten years ago, there was nothing cuter than Amanda Bynes, the absolute It-Girl of the early 2000s and a bright beacon in a dark world for those of us who were going through puberty very poorly. Something about her off-beat Nickelodeon charm spoke to a generation of girls who knew we weren’t Disney Star material, and nowhere did this shine brighter than in future cult classic She’s the Man.

For those of you who very sadly missed out on this one in the sea of endless mid-2000s upbeat teen comedies, She’s the Man is an (albeit pretty loose) adaptation of Twelfth Night, but with teenagers and soccer instead of mid-20-somethings and…whatever it is all these people in Twelfth Night do for fun. When I first saw this movie, I was an awkward teenager who knew a lot about The Amanda Showand nothing about Twelfth Night, so I was probably exactly the kind of person for whom this film was made. For purposes of this rewatch, I am a slightly-less-awkward adult staring down the barrel of entering my late 20s on Monday, and I know a lot about what happens to Amanda Bynes after this movie is made, andTwelfth Night and I have a complicated relationship thanks to a lot of bad scene work in theatre school.

But honestly, who doesn’t want to watch a movie where Amanda Bynes goes undercover in an attempt to dismantle the patriarchy from within?

She’s the Man jumps right to the plot: Viola (Amanda Bynes) is a powerhouse soccer player at Cornwall High School—that is, until The Patriarchy shuts down the girls’ soccer team, and Coach McDouche won’t let any of them join the boys’ team because apparently girls are shittier athletes. Amanda appeals to her Toolbag Goalkeeper boyfriend, who admitted yesterday that she was “probably better than half the guys on the team,” (“Maybe more than half,” Amanda replies sweetly, reminding him—and us—that she’s not here for your bullshit and will not have her accomplishments diminished by your assumptions about her gender) but Toolbag refuses to stick up for her and laughs with the other boys that girls aren’t good enough at sports.

Amanda responds by promptly dumping him and beaning him the face with her soccer ball. I can tell already that I’m going to love this movie just as much as I did in 2006.

“How can I prevent Fragile Masculinity from standing in the way of my dreams?”

Not wanting to waste any time (seriously, we’re like maybe five minutes into the movie) we receive the entire rest of the setup: Amanda is mistaken from behind for her twin brother, Sebastian (whose real name, shit you not, is James Kirk), Amanda’s mother demands that Amanda attend a Debutante Ball but Amanda is too busy dismantling the patriarchy to deal with this shit, and Sebastian is running away to London for two weeks to do some kind of rock star teen thing that I didn’t really understand—right before he’s meant to transfer to Illyria High School, which (wouldn’t you know it?) is Cornwall’s biggest rival in soccer.

I’d forgotten how fast movies used to move in that era, because I’m pretty sureTwelfth Night took a lot longer to get us this much info, but Amanda has a lot of men to step on in her climb to the top, so she’s not here to wait around. She quickly concocts a plan to dress as Sebastian, infiltrate Illyria’s soccer team, and kick Cornwall’s ass, to prove to Coach McDouche that girls are to be taken seriously as athletes—to do this, she’s going to need guitar-powered montage of haircuts and Manwalking, which I’m pretty sure is just Amanda Bynes having fun with props and strangers as only Amanda can.

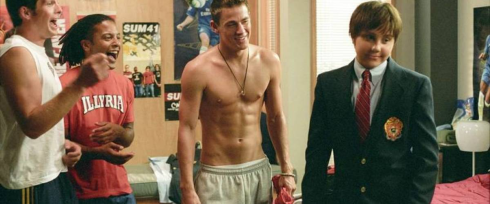

First day at Illyria High School, and we meet pretty much the best thing ever: Baby Channing Tatum! He has no idea he’s going to be the most famous man on the planet in just a few short years! Look at how adorable he is! I just wanna squish his little baby Channing Tatum face!

*Swoon.*

Amanda defuses America’s collective sexual awakening by instructing her new roommates how to stop nosebleeds by putting tampons in your nose, and to be honest, this sounds like a great idea—has anyone ever tried this?

On to the real reason we’re here: Illyria’s soccer team, coached by Gareth fromGalavant, and yes, he’s literally exactly what you would expect from Coach Gareth—gruff as fuck but ultimately the best: when Amanda announces that she must keep her shirt on during practice because she is “allergic to the sun,” Coach Gareth barks some guff at her but doesn’t push the issue and never brings it up again, because he’s the only gym teacher in the world who cares about your needs as a person.

Tobias Funke is the principal of Illyria High School, which goes exactly how you expect it will. I’m not sure of his function in the story or which character inTwelfth Night he’s meant to be, but honestly, all the supporting characters are getting pretty fuzzy by now because we didn’t really want to commit to the Shakespeare thing all the way through. There’s about half a dozen friends of Amanda and BCT that have yet to be named, but they’re probably some combination of Mariah/Sir Toby/Antonio/Whathaveyou.

On her way out of Principal Funke’s office, Amanda smacks into a hot blonde girl named Olivia, and experiences teenage sexual tension. I’m instantly regretting that this movie isn’t about Amanda Bynes discovering men are the worst and embracing her bisexuality, because while I am all about Baby Channing Tatum, I feel this would’ve been a way more interesting twist on the story. But maybe that’s just me.

The boys start doing that thing that boys do when there aren’t women around: being fucking gross about women. To his credit, Baby Channing Tatum refuses to participate, because he’s ~*different*~ but still doesn’t do a lot to derail the discussions his friends are having. You have a lot of work to do, Baby Channing Tatum. But he does spend a lot of time wearing boxers that are clinging to his hips like Sly Stallone in Cliffhanger.

i.e. not well.

Unlike how I felt actually watching Cliffhanger, I’m far from disappointed. (Ed. Cliffhanger rules and John Lithgow will get you yet, Kiki.)

*Swoon.*

In what proves to be the most unexpectedly terrifying scene in the movie, four men arrive in the middle of the night and kidnap Amanda and take her to a dark room, where all the new soccer players are instructed to take off their clothes for a hazing ritual. As a teenager observing this, I remember thinking “Shit, Amanda, how are you gonna get out of THIS wacky happenstance?” (answer: pulling a fire alarm and crawling out a side door, which is the ultimate get-out-of-jail-free card of teen media.) As an adult, I got SUPER uncomfortable—being a teenage girl and being dragged from your bed by masked strangers bigger than you who demand you get naked in front of them IS FUCKING TERRIFYING. I’ve never been a boy, so I can’t speak to how scary that would be for them, but as a girl, I found this scene pretty disturbing, and am amazed that Amanda was chill around these guys the next day, rather than feeling terrified that her friends gave so little of a shit about her bodily autonomy. Maybe it’s because she knows she’s about to detonate a truth bomb so big it will rattle the very core of their Masculinity. But I probably would’ve never spoken to a single one of those assholes again tbh.

But then comes what is probably the most HOPELESSLY MISGUIDED part of the movie: In order to prove her worth to shitty boys, Amanda gets her friends to participate in a montage of hot women hitting on her, to prove to these guys she has ‘game.’ Okay, fine, this is dumb, but whatever. It works, and Baby Channing Tatum and co. are instantly changing their tune—until Sebastian’s real-life girlfriend Monique shows up, and they get gross at her. Monique responds with the best comeback of all time: “Girls with asses like mine do not date boys with faces like yours.” TEAM MONIQUE 2K16.

Unfortunately, Amanda has proven in scenes past that she hates Monique for reasons unknown (so far all she’s done is stand up for herself and wear pink, but everyone is being super rude to her?) As part of her Manly Man persona, Amanda must humiliate her in order to continue participating in the patriarchy, and Monique is heartbroken. As am I. I’m on your side, Monique. You deserved better than what happened to you today. But you made the mistake of being the hot strawberry-blonde in a mid-2000s teen film, which means you’re the bad guy for some reason. Your day will come, girl.

Dismantling the patriarchy also involves dismantling internalized misogyny, ladies. Monique is a victim here.

Amanda is now ‘in’ with the dudes, and she gets exactly what we’d expect: men being gross about girls, mansplaining, and waggling their penises in her face. Amanda reacts appropriately by hating all of them, and only hanging out with her lab partner, Hot Blonde Olivia from earlier. But all the bubbling chemistry sets in the world can’t show Amanda how to deal with the chemistry she has with Olivia, whose heart she breaks by blurting out that she’s not into her. </3 Team Violivia 2K16.

SURPRISE! Sebastian and Viola are BOTH expected at some kind of carnival thing! Says Amanda’s mom! I have no idea what the carnival is for, but both Cornwall and Illyria kids are going! And Olivia and Viola are both signed up to run the kissing booth BY THEIR MOTHERS which is hella gross and a great way to catch herpes! Over the next ten minutes, Amanda participates in some Mrs. Doubtfire costume-change hijinks, Channing Tatum offers to drown in Toolbag Boyfriend’s male tears, Amanda Bynes falls in love with Baby Channing Tatum, and Monique continues to refuse to stand for this treatment. For a plot point that makes no sense, there’s a lot of great shit happening here.

Thanks to Channing Tatum’s ‘How to Zlatan Ibrahimovic’ montage, Amanda is now hella good at Bicycle Kicks, so Coach Gareth bumps her up to first string; she celebrates as anyone would, which is attempting to touch Channing Tatum’s butt. Olivia decides to make Amanda Bynes jealous by asking Channing Tatum out. It works, but not the way she wants. I’m feeling the way about this movie I did throughout both Pitch Perfects: the heterosexual lead couple isn’t NEARLY as interesting as the obvious lesbian undertones between the leading lady and her new hot best friend.

Amanda, Olivia, and Monique are all apparently part of this Debutante ball thing, which makes this the second Amanda Bynes film in three years where her being a reluctant debutante is a major part of the plot (for further study, please see the spectacular Cinderella story What a Girl Wants, starring Amanda and Colin Fucking Firth in Leather Fucking Pants.) Amanda’s mom is super into it, but Amanda isn’t: “I will not wear heels. Because heels are a male invention designed to make a woman’s butt look smaller. And to make it harder to run away.” You tell ‘em, Amanda.

This scene ends in a horrible pastel catfight in the bathroom where everyone gangs up on Queen Monique, but I only bring it up because of this moment, which I had forgotten about, which made me laugh so hard I startled two cats off my lap and choked on my beer.

Olivia speaks to whatever random side character this is supposed to be (we’ve stopped giving people names so we don’t have to admit we didn’t read the play) and decides she needs to just kiss Sebastian on the face and admit that she loves him—that won’t be bad, right? EXCEPT THAT ISN’T AMANDA BYNES, IT’S CAPTAIN JAMES T. KIRK, THE REAL SEBASTIAN, AND BABY CHANNING TATUM SAW AND NOW HE’S SUPER SAD AND SAD CHANNING TATUM IS VERY HARD TO WATCH. Poor precious baby. I’ll be honest, I didn’t really ‘Get’ Channing Tatum before rewatching this movie, but having seen it a second time, I totally understand what everyone’s been going on about. He is a precious baby bunny and deserves to be protected from sadness and teenage angst.

James T. Kirk has no idea what’s going on, but decides to just go along with this new world order, including participating in the Big Soccer Game Against Cornwall because Amanda didn’t wake up on time for some reason. James T. Kirk is a shitty soccer player, but he’s too good-natured to work out what’s happening, and is subsequently benched; Amanda is furious, particularly once Principal Funke arrives with a megaphone and accuses him of being a girl, at which point James T. Kirk flashes his wang at a stadium full of people he’s just met, because fuck you for attempting to out a person in public.

Amanda is dying behind the stands, so at half time, she angrily switches outfits with her brother and heads to the pitch, where Coach Gareth is skeptical but breaks the rules of soccer by allowing a benched player back onto the field; I don’t think the ref is watching the same game I am, because Baby Channing Tatum earns several red cards by assaulting Cornwall players off the ball and no one calls him on it. Apparently the ref hates Cornwall and doesn’t give a shit if you abuse them. Apparently Cornwall is the Seattle Sounders of this world. I’m just saying.

Due to Monique’s effective and underappreciated indictment of the patriarchy, Amanda is forced to reveal at last her true identity—by, of course, nonchalantly flashing her boobs and demanding everyone shut the fuck up, at which point Coach Douche demands that we forfeit the game because there’s a lady on the field. Coach Gareth rips a sports manual in half and demands an end to sexism on his soccer field, because he’s the fucking best.

“Breasts are not sex organs, Members of the Patriarchy. I have no fear of sharing them with you. #freethenipple”

What follows is actually some pretty legit soccer—like, not Bend It Like Beckhamgood, but still pretty legit. No one gives a shit that Amanda is a lady, because her dismantling of the patriarchy has succeeded, and her teammates are cool now. Amanda Dares to Zlatan and bicycle kicks the shit out of the winning goal, and everyone celebrates, except Toolbag Boyfriend who does what all shitty rejected boys do: crying hysterically while screaming insults at her and accusing the world of injustice. Amanda dgaf and rises above his nonsense, introducing James T. Kirk to Hot Olivia, who decides quashing her budding sexuality is more important than her indignation over having been deceived, because she runs off with him immediately to escape her feelings for Amanda Bynes. </3 RIP Violivia.

On the day of the Debutante Ball, Mom has decided she also wants to dismantle the patriarchy: “You don’t need a man to wear a beautiful dress,” she announces, and I’m pretty into it. Amanda wanders off alone into some spooky woods to deal with her budding sexuality over seeing Olivia all dolled up. She runs into Baby Channing Tatum, who admits he misses his new best friend, because it turns out actually being friends with a girl can be a lot of fun, and admits that he probably would’ve been shittier to her if he’d known she was a lady, because Men are the Absolute Worst. Amanda forgives his sweet, stupid self, and they live happily ever after, presumably, now that Amanda has converted him and all his friends to feminism.

Honestly, this movie wasn’t what I was expecting on a second watch. I sort of thought it would be a night of “Awww, I remember liking this when I was younger, but oof, the mid 2000s were a weird time.” But actually, I think I like this movie BETTER than I did the first time. There’s a lot of Grade A feminism going on in this movie, a lot of which I was too young to really appreciate when I first saw it—and there’s also some Grade A Patriarchal Bullshit happening, i.e. our horrific treatment of Monique, which I was also too young to understand at the time. Apparently these screenwriters didn’t learn enough from then-recent smash hitMean Girls.